Did you know that one in 10 babies globally are born too soon every year?

This equates to about 15 million of the world’s babies born before 37 weeks’ gestations. More than two million of these babies are born very preterm (less than 32 weeks’) and are at an increased risk of chronic lung disease.

The Wal-yan Respiratory Research Centre – a powerhouse partnership between The Kids Research Institute Australia, Perth Children’s Hospital Foundation and Perth Children’s Hospital – has many researchers who are dedicated to understanding the impact of premature birth on lung health.

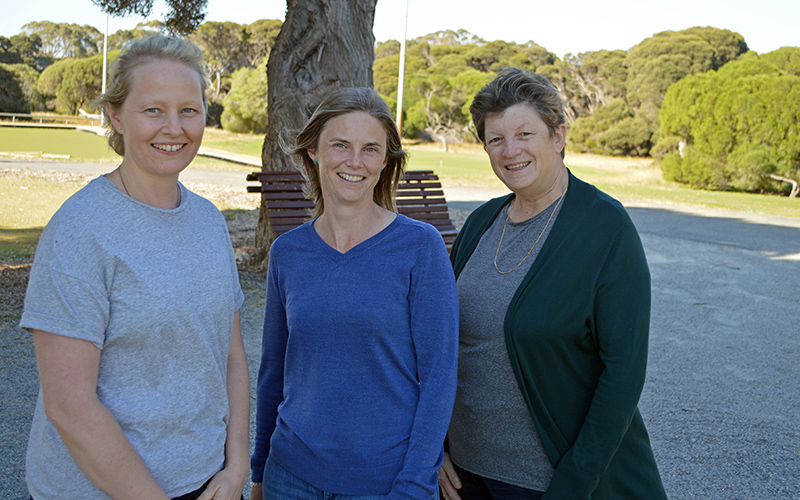

This World Prematurity Day, Wal-yan Centre researchers Professor Jane Pillow and Dr Shannon Simpson along with consumer advocate Amber Bates share why they became involved in preterm respiratory health and what this day means to them.

Professor Jane Pillow is an academic neonatologist with The University of Western Australia who has an active clinical and preclinical research program. Prof Pillow also leads the Neonatal Cardiorespiratory Health team at the Wal-yan Centre.

Dr Shannon Simpson, who is head of the Children’s Lung Health team at the Wal-yan Centre, has been instrumental in researching the long-term respiratory issues faced by people born prematurely. She is also an Associate Professor with Curtin University.

Amber Bates is a mother of four children, whose youngest child was born very prematurely. Ms Bates is the chairperson and co-founder of Tiny Sparks WA, a support group for families with children born preterm, and has been a long-term member of Wal-yan Centre’s Preterm Community Reference Group.

What motivated you to want to do preterm health research?

Prof Pillow:

I had always planned to be a researcher, but actually just fell into preterm research. I was filling in time before moving to Vietnam when our move was delayed, and I started researching a novel way to help premature babies to breathe. Essentially, the new ventilator gently vibrated the lungs of the premature babies, to help oxygen get into the lungs and to help remove the waste gas from the body. I was fascinated by the mathematics and engineering behind the unique way this ventilator worked, and its potential to prevent injury in the preterm lung. I realised that I had a rare talent to investigate and understand some of these complex principles, and importantly also to explain them simply to my clinician colleagues and to parents.

Dr Simpson:

My PhD looked at the lung development of marsupials and became intrigued about why marsupials (who would be incredibly preterm by human standards!) are able to survive and thrive, and yet human babies born at a comparable gestation did not survive.

Also, I am blown away by the “fighter attitudes” of children who are born prematurely.

Ms Bates:

Our youngest son was born very prematurely at just 25 weeks gestational age. He overcame many hurdles during his long NICU (Neonatal Intensive Care Unit) stay but by far his biggest challenge was chronic lung disease, which saw him need extra oxygen at home until he was about 18 months old.

During his early years we had many readmissions to hospital as his lungs just couldn’t cope with the usual viruses kids’ catch but generally bounce back quickly from. When the opportunity arose to join the Preterm Community Reference Group I applied because I wanted to help researchers find answers for kids like mine.

You’ve done a lot of work in preterm health space, but in a nutshell how has your work contributed to respiratory health of children born prematurely?

Prof Pillow:

A lot of my research has focused on understanding how different methods of respiratory support can help babies to breathe without damaging their lungs. Through my research, I have been able to teach many clinicians around the world how to look after preterm infants with lung disease, using lung protective respiratory support to minimise any damage to the fragile lungs of preterm infants in their care.

Dr Simpson:

We have discovered that lung health is deteriorating throughout childhood for some survivors of preterm birth. We have also started to elucidate the biological mechanisms underpinning such reduction in lung function over time.

Why does this research matter?

Prof Pillow:

Premature babies are born before their lungs finish developing. Damage to the lungs during this early stage of development can cause them to stop growing, and may cause chronic lung disease of prematurity.

Chronic lung disease after premature birth may be a life-long health problem for these babies as they become children and then adults, and can limit their enjoyment and ability to fully participate in normal life activities.

Dr Simpson:

While this might initially sound scary for families, the research has opened up the possibility of developing ways to identify which children will have better or poorer outcomes and to develop interventions to make sure every child born preterm can live their best life.

It is also being used to inform clinical practice and advocate for co-ordinated respiratory follow up for those graduating from the NICU.

Ms Bates:

One in 10 children are born prematurely, representing a staggering 15 million babies born early, worldwide, each year. Prematurity can impact ANY family. The very important lifesaving measures taken in NICU can have lifelong consequences.

Children born early deserve the best opportunity to grow up healthy and happy just like other kids. When you know better, do better - research is an opportunity to find out what ‘better’ is.

Today is World Prematurity Day, what does it mean to you?

Prof Pillow:

World Prematurity Day is a reminder that around the world, over 15 million babies are born too soon. Being born early places huge burdens on health systems, families, and most importantly - on the preterm infants themselves. This day focuses attention on the challenges faced by those born preterm, and their families, and provides us with an opportunity to commit to change their lives for the better.

Dr Simpson:

For me it’s a day to engage with the children and families who have been affected by preterm birth. It’s a reminder that we have come so far but that there is so much work for us to do to help these kids and their families – and to honour the individual journey that each family is on.

Today is an opportunity to raise awareness and to advocate for better outcomes for babies born preterm.

Ms Bates:

Today means so many things! It is an opportunity to shine a light on the critical issue of preterm birth and raise awareness in the community, not just locally but globally.

Seeing so many buildings and landmarks lit purple (purple is the colour associated with preterm birth) all over the world is really something. It’s a reminder that this is something bigger than any one individual, project or organisation. It’s a moment to pause and reflect on our personal journey, celebrate our son and encourage other families to do similar.

What are you most proud of?

Prof Pillow:

That is a really difficult question! There are so many things to be proud of - but mostly I am proud of being part of a global team of researchers committed to making the lives of preterm infants and their families better - through better treatments, and educating carers about how best to care for these vulnerable infants.

Dr Simpson:

I am proud that I have been able to bring together an integrative collaborative network of researchers, clinicians and the community to think big and work together to answer the big questions.

Also, I’m really proud of my whole team for being on this journey with me and for supporting this vision.

Ms Bates:

I am most proud of the resilience and determination my family has shown in the face of adversity.

In spite of a long NICU stay, multiple hospital admissions, surgeries, countless outpatient appointments, early intervention, the list goes on – we not just survived but thrived!

We’ve been able to build a community to support others through Tiny Sparks and we’ve been able to give back by participating in research and contributing to committees and projects locally, nationally and internationally.

What’s next for your research?

Prof Pillow:

Right now I am really excited about a potentially very simple intervention that might help baby’s lungs to grow and function better and protect them from repeated lung infections during life. Essentially, we are looking at how early development of a daily (circadian) rhythm after preterm birth might promote normal lung development and protect the infants from viral respiratory tract infections during childhood.

We believe that preventing respiratory tract infections in childhood is essential to prevent the decline in lung function that many preterm children have throughout their schooling years, and the resulting life-long problems with breathing that they have.

Dr Simpson:

We are getting close to winding up the first interventional trial aimed to improve childhood lung health for survivors of very preterm birth. We are working toward getting interventions to improve lung health into the clinic, getting education about later lung health out to families and doctors in primary care (GPs).

I am also co-leading a global preterm data sharing consortium (PELICAN) so that we can use big data and a big collaborative network to get better outcomes for these kids.